Application Containerization and Microservice Orchestration

In this tutorial we will learn about basic application containerization using Docker and running various components of an application as microservices. We will utilize Docker Compose for orchestration during the development. This tutorial is targeted for beginners who have the basic familiarity with Docker. If you are new to Docker, we recommend you check out Docker Basics for Linux tutorial first.

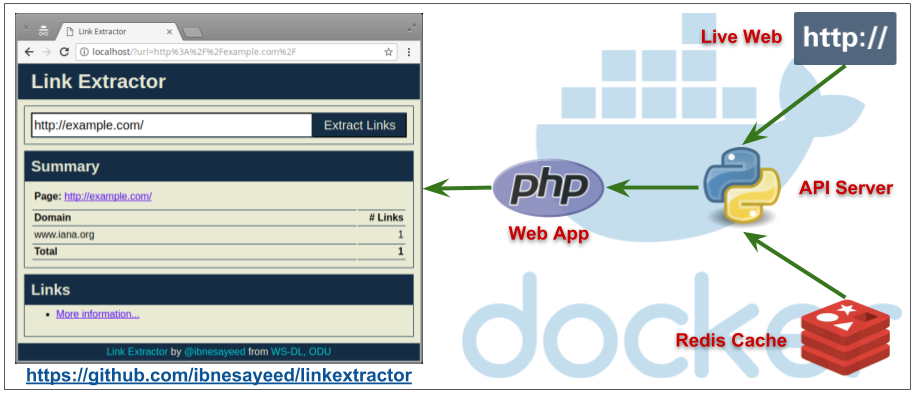

We will start from a basic Python script that scrapes links from a given web page and gradually evolve it into a multi-service application stack. The demo code is available in the Link Extractor repo. The code is organized in steps that incrementally introduce changes and new concepts. After completion, the application stack will contain the following microservices:

- A web application written in PHP and served using Apache that takes a URL as the input and summarizes extracted links from it

- The web application talks to an API server written in Python (and Ruby) that takes care of the link extraction and returns a JSON response

- A Redis cache that is used by the API server to avoid repeated fetch and link extraction for pages that are already scraped

The API server will only load the page of the input link from the web if it is not in the cache. The stack will eventually look like the figure below:

This tutorial was initially developed for a colloquium in the Computer Science Department of the Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia. A video recording, presentation slides, and a brief description of the talk can be found in a blog post.

Steps:

- Stage Setup

- Step 0: Basic Link Extractor Script

- Step 1: Containerized Link Extractor Script

- Step 2: Link Extractor Module with Full URI and Anchor Text

- Step 3: Link Extractor API Service

- Step 4: Link Extractor API and Web Front End Services

- Step 5: Redis Service for Caching

- Step 6: Swap Python API Service with Ruby

- Conclusions

Stage Setup

Let’s get started by first cloning the demo code repository, changing the working directory, and checking the demo branch out.

git clone https://github.com/ibnesayeed/linkextractor.git

cd linkextractor

git checkout demo

Step 0: Basic Link Extractor Script

Checkout the step0 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step0

tree

.

├── README.md

└── linkextractor.py

0 directories, 2 files

The linkextractor.py file is the interesting one here, so let’s look at its contents:

cat linkextractor.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

res = requests.get(sys.argv[-1])

soup = BeautifulSoup(res.text, "html.parser")

for link in soup.find_all("a"):

print(link.get("href"))

This is a simple Python script that imports three packages: sys from the standard library and two popular third-party packages requests and bs4.

User-supplied command line argument (which is expected to be a URL to an HTML page) is used to fetch the page using the requests package, then parsed using the BeautifulSoup.

The parsed object is then iterated over to find all the anchor elements (i.e., <a> tags) and print the value of their href attribute that contains the hyperlink.

However, this seemingly simple script might not be the easiest one to run on a machine that does not meet its requirements.

The README.md file suggests how to run it, so let’s give it a try:

./linkextractor.py http://example.com/

bash: ./linkextractor.py: Permission denied

When we tried to execute it as a script, we got the Permission denied error.

Let’s check the current permissions on this file:

ls -l linkextractor.py

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 220 Sep 23 16:26 linkextractor.py

This current permission -rw-r--r-- indicates that the script is not set to be executable.

We can either change it by running chmod a+x linkextractor.py or run it as a Python program instead of a self-executing script as illustrated below:

python linkextractor.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "linkextractor.py", line 5, in <module>

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

ImportError: No module named bs4

Here we got the first ImportError message because we are missing the third-party package needed by the script.

We can install that Python package (and potentially other missing packages) using one of the many techniques to make it work, but it is too much work for such a simple script, which might not be obvious for those who are not familiar with Python’s ecosystem.

Depending on which machine and operating system you are trying to run this script on, what software is already installed, and how much access you have, you might face some of these potential difficulties:

- Is the script executable?

- Is Python installed on the machine?

- Can you install software on the machine?

- Is

pipinstalled? - Are

requestsandbeautifulsoup4Python libraries installed?

This is where application containerization tools like Docker come in handy. In the next step we will try to containerize this script and make it easier to execute.

Step 1: Containerized Link Extractor Script

Checkout the step1 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step1

tree

.

├── Dockerfile

├── README.md

└── linkextractor.py

0 directories, 3 files

We have added one new file (i.e., Dockerfile) in this step.

Let’s look into its contents:

cat Dockerfile

FROM python:3

LABEL maintainer="Sawood Alam <@ibnesayeed>"

RUN pip install beautifulsoup4

RUN pip install requests

WORKDIR /app

COPY linkextractor.py /app/

RUN chmod a+x linkextractor.py

ENTRYPOINT ["./linkextractor.py"]

Using this Dockerfile we can prepare a Docker image for this script.

We start from the official python Docker image that contains Python’s run-time environment as well as necessary tools to install Python packages and dependencies.

We then add some metadata as labels (this step is not essential, but is a good practice nonetheless).

Next two instructions run the pip install command to install the two third-party packages needed for the script to function properly.

We then create a working directory /app, copy the linkextractor.py file in it, and change its permissions to make it an executable script.

Finally, we set the script as the entrypoint for the image.

So far, we have just described how we want our Docker image to be like, but didn’t really build one. So let’s do just that:

docker image build -t linkextractor:step1 .

This command should yield an output as illustrated below:

Sending build context to Docker daemon 171.5kB

Step 1/8 : FROM python:3

... [OUTPUT REDACTED] ...

Successfully built 226196ada9ab

Successfully tagged linkextractor:step1

We have created a Docker image named linkextractor:step1 based on the Dockerfile illustrated above.

If the build was successful, we should be able to see it in the list of image:

docker image ls

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

linkextractor step1 e067c677be37 2 seconds ago 931MB

python 3 a9d071760c82 2 weeks ago 923MB

This image should have all the necessary ingredients packaged in it to run the script anywhere on a machine that supports Docker. Now, let’s run a one-off container with this image and extract links from some live web pages:

docker container run -it --rm linkextractor:step1 http://example.com/

This outputs a single link that is present in the simple example.com web page:

http://www.iana.org/domains/example

Let’s try it on a web page with more links in it:

docker container run -it --rm linkextractor:step1 https://training.play-with-docker.com/

/

/about/

#ops

#dev

/ops-stage1

/ops-stage2

/ops-stage3

/dev-stage1

/dev-stage2

/dev-stage3

/alacart

https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Play with Docker Classroom&url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/&via=docker&related=docker

https://facebook.com/sharer.php?u=https://training.play-with-docker.com/

https://plus.google.com/share?url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/

http://www.linkedin.com/shareArticle?mini=true&url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/&title=Play%20with%20Docker%20Classroom&source=https://training.play-with-docker.com

https://2018.dockercon.com/

https://2018.dockercon.com/

https://success.docker.com/training/

https://community.docker.com/registrations/groups/4316

https://docker.com

https://www.docker.com

https://www.facebook.com/docker.run

https://twitter.com/docker

https://www.github.com/play-with-docker/play-with-docker.github.io

This looks good, but we can improve the output. For example, some links are relative, we can convert them into full URLs and also provide the anchor text they are linked to. In the next step we will make these changes and some other improvements to the script.

Step 2: Link Extractor Module with Full URI and Anchor Text

Checkout the step2 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step2

tree

.

├── Dockerfile

├── README.md

└── linkextractor.py

0 directories, 3 files

In this step the linkextractor.py script is updated with the following functional changes:

- Paths are normalized to full URLs

- Reporting both links and anchor texts

- Usable as a module in other scripts

Let’s have a look at the updated script:

cat linkextractor.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from urllib.parse import urljoin

def extract_links(url):

res = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(res.text, "html.parser")

base = url

# TODO: Update base if a <base> element is present with the href attribute

links = []

for link in soup.find_all("a"):

links.append({

"text": " ".join(link.text.split()) or "[IMG]",

"href": urljoin(base, link.get("href"))

})

return links

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("\nUsage:\n\t{} <URL>\n".format(sys.argv[0]))

sys.exit(1)

for link in extract_links(sys.argv[-1]):

print("[{}]({})".format(link["text"], link["href"]))

The link extraction logic is abstracted into a function extract_links that accepts a URL as a parameter and returns a list of objects containing anchor texts and normalized hyperlinks.

This functionality can now be imported into other scripts as a module (which we will utilize in the next step).

Now, let’s build a new image and see these changes in effect:

docker image build -t linkextractor:step2 .

We have used a new tag linkextractor:step2 for this image so that we don’t overwrite the image from the step0 to illustrate that they can co-exist and containers can be run using either of these images.

docker image ls

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

linkextractor step2 be2939eada96 3 seconds ago 931MB

linkextractor step1 673d045a822f About a minute ago 931MB

python 3 a9d071760c82 2 weeks ago 923MB

Running a one-off container using the linkextractor:step2 image should now yield an improved output:

docker container run -it --rm linkextractor:step2 https://training.play-with-docker.com/

[Play with Docker classroom](https://training.play-with-docker.com/)

[About](https://training.play-with-docker.com/about/)

[IT Pros and System Administrators](https://training.play-with-docker.com/#ops)

[Developers](https://training.play-with-docker.com/#dev)

[Stage 1: The Basics](https://training.play-with-docker.com/ops-stage1)

[Stage 2: Digging Deeper](https://training.play-with-docker.com/ops-stage2)

[Stage 3: Moving to Production](https://training.play-with-docker.com/ops-stage3)

[Stage 1: The Basics](https://training.play-with-docker.com/dev-stage1)

[Stage 2: Digging Deeper](https://training.play-with-docker.com/dev-stage2)

[Stage 3: Moving to Staging](https://training.play-with-docker.com/dev-stage3)

[Full list of individual labs](https://training.play-with-docker.com/alacart)

[[IMG]](https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Play with Docker Classroom&url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/&via=docker&related=docker)

[[IMG]](https://facebook.com/sharer.php?u=https://training.play-with-docker.com/)

[[IMG]](https://plus.google.com/share?url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/)

[[IMG]](http://www.linkedin.com/shareArticle?mini=true&url=https://training.play-with-docker.com/&title=Play%20with%20Docker%20Classroom&source=https://training.play-with-docker.com)

[[IMG]](https://2018.dockercon.com/)

[DockerCon 2018 in San Francisco](https://2018.dockercon.com/)

[training.docker.com](https://success.docker.com/training/)

[Register here](https://community.docker.com/registrations/groups/4316)

[Docker, Inc.](https://docker.com)

[[IMG]](https://www.docker.com)

[[IMG]](https://www.facebook.com/docker.run)

[[IMG]](https://twitter.com/docker)

[[IMG]](https://www.github.com/play-with-docker/play-with-docker.github.io)

Running a container using the previous image linkextractor:step1 should still result in the old output:

docker container run -it --rm linkextractor:step1 https://training.play-with-docker.com/

So far, we have learned how to containerize a script with its necessary dependencies to make it more portable. We have also learned how to make changes in the application and build different variants of Docker images that can co-exist. In the next step we will build a web service that will utilize this script and will make the service run inside a Docker container.

Step 3: Link Extractor API Service

Checkout the step3 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step3

tree

.

├── Dockerfile

├── README.md

├── linkextractor.py

├── main.py

└── requirements.txt

0 directories, 5 files

The following changes have been made in this step:

- Added a server script

main.pythat utilizes the link extraction module written in the last step - The

Dockerfileis updated to refer to themain.pyfile instead - Server is accessible as a WEB API at

http://<hostname>[:<prt>]/api/<url> - Dependencies are moved to the

requirements.txtfile - Needs port mapping to make the service accessible outside of the container (the

Flaskserver used here listens on port5000by default)

Let’s first look at the Dockerfile for changes:

cat Dockerfile

FROM python:3

LABEL maintainer="Sawood Alam <@ibnesayeed>"

WORKDIR /app

COPY requirements.txt /app/

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

COPY *.py /app/

RUN chmod a+x *.py

CMD ["./main.py"]

Since we have started using requirements.txt for dependencies, we no longer need to run pip install command for individual packages.

The ENTRYPOINT directive is replaced with the CMD and it is referring to the main.py script that has the server code it because we do not want to use this image for one-off commands now.

The linkextractor.py module remains unchanged in this step, so let’s look into the newly added main.py file:

cat main.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

from flask import Flask

from flask import request

from flask import jsonify

from linkextractor import extract_links

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def index():

return "Usage: http://<hostname>[:<prt>]/api/<url>"

@app.route("/api/<path:url>")

def api(url):

qs = request.query_string.decode("utf-8")

if qs != "":

url += "?" + qs

links = extract_links(url)

return jsonify(links)

app.run(host="0.0.0.0")

Here, we are importing extract_links function from the linkextractor module and converting the returned list of objects into a JSON response.

It’s time to build a new image with these changes in place:

docker image build -t linkextractor:step3 .

Then run the container in detached mode (-d flag) so that the terminal is available for other commands while the container is still running.

Note that we are mapping the port 5000 of the container with the 5000 of the host (using -p 5000:5000 argument) to make it accessible from the host.

We are also assigning a name (--name=linkextractor) to the container to make it easier to see logs and kill or remove the container.

docker container run -d -p 5000:5000 --name=linkextractor linkextractor:step3

If things go well, we should be able to see the container being listed in Up condition:

docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUSPORTS NAMES

d69c0150a754 linkextractor:step3 "./main.py" 9 seconds ago Up 8 seconds0.0.0.0:5000->5000/tcp linkextractor

We can now make an HTTP request in the form /api/<url> to talk to this server and fetch the response containing extracted links:

curl -i http://localhost:5000/api/http://example.com/

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 78

Server: Werkzeug/0.14.1 Python/3.7.0

Date: Sun, 23 Sep 2018 20:52:56 GMT

[{"href":"http://www.iana.org/domains/example","text":"More information..."}]

Now, we have the API service running that accepts requests in the form /api/<url> and responds with a JSON containing hyperlinks and anchor texts of all the links present in the web page at give <url>.

Since the container is running in detached mode, so we can’t see what’s happening inside, but we can see logs using the name linkextractor we assigned to our container:

docker container logs linkextractor

* Serving Flask app "main" (lazy loading)

* Environment: production

WARNING: Do not use the development server in a production environment.

Use a production WSGI server instead.

* Debug mode: off

* Running on http://0.0.0.0:5000/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

172.17.0.1 - - [23/Sep/2018 20:52:56] "GET /api/http://example.com/ HTTP/1.1" 200 -

We can see the messages logged when the server came up, and an entry of the request log when we ran the curl command.

Now we can kill and remove this container:

docker container rm -f linkextractor

In this step we have successfully ran an API service listening on port 5000.

This is great, but APIs and JSON responses are for machines, so in the next step we will run a web service with a human-friendly web interface in addition to this API service.

Step 4: Link Extractor API and Web Front End Services

Checkout the step4 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step4

tree

.

├── README.md

├── api

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── linkextractor.py

│ ├── main.py

│ └── requirements.txt

├── docker-compose.yml

└── www

└── index.php

2 directories, 7 files

In this step the following changes have been made since the last step:

- The link extractor JSON API service (written in Python) is moved in a separate

./apifolder that has the exact same code as in the previous step - A web front-end application is written in PHP under

./wwwfolder that talks to the JSON API - The PHP application is mounted inside the official

php:7-apacheDocker image for easier modification during the development - The web application is made accessible at

http://<hostname>[:<prt>]/?url=<url-encoded-url> - An environment variable

API_ENDPOINTis used inside the PHP application to configure it to talk to the JSON API server - A

docker-compose.ymlfile is written to build various components and glue them together

In this step we are planning to run two separate containers, one for the API and the other for the web interface. The latter needs a way to talk to the API server. For the two containers to be able to talk to each other, we can either map their ports on the host machine and use that for request routing or we can place the containers in a single private network and access directly. Docker has an excellent support of networking and provides helpful commands to deal with networks. Additionally, in a Docker network containers identify themselves using their names as hostnames to avoid hunting for their IP addresses in the private network. However, we are not going to do any of this manually, instead we will be using Docker Compose to automate many of these tasks.

So let’s look at the docker-compose.yml file we have:

cat docker-compose.yml

version: '3'

services:

api:

image: linkextractor-api:step4-python

build: ./api

ports:

- "5000:5000"

web:

image: php:7-apache

ports:

- "80:80"

environment:

- API_ENDPOINT=http://api:5000/api/

volumes:

- ./www:/var/www/html

This is a simple YAML file that describes the two services api and web.

The api service will use the linkextractor-api:step4-python image that is not built yet, but will be built on-demand using the Dockerfile from the ./api directory.

This service will be exposed on the port 5000 of the host.

The second service named web will use official php:7-apache image directly from the DockerHub, that’s why we do not have a Dockerfile for it.

The service will be exposed on the default HTTP port (i.e., 80).

We will supply an environment variable named API_ENDPOINT with the value http://api:5000/api/ to tell the PHP script where to connect to for the API access.

Notice that we are not using an IP address here, instead, api:5000 is being used because we will have a dynamic hostname entry in the private network for the API service matching its service name.

Finally, we will bind mount the ./www folder to make the index.php file available inside of the web service container at /var/www/html, which is the default web root for the Apache web server.

Now, let’s have a look at the user-facing www/index.php file:

cat www/index.php

This is a long file that mainly contains all the markup and styles of the page. However, the important block of code is in the beginning of the file as illustrated below:

$api_endpoint = $_ENV["API_ENDPOINT"] ?: "http://localhost:5000/api/";

$url = "";

if(isset($_GET["url"]) && $_GET["url"] != "") {

$url = $_GET["url"];

$json = @file_get_contents($api_endpoint . $url);

if($json == false) {

$err = "Something is wrong with the URL: " . $url;

} else {

$links = json_decode($json, true);

$domains = [];

foreach($links as $link) {

array_push($domains, parse_url($link["href"], PHP_URL_HOST));

}

$domainct = @array_count_values($domains);

arsort($domainct);

}

}

The $api_endpoint variable is initialized with the value of the environment variable supplied from the docker-compose.yml file as $_ENV["API_ENDPOINT"] (otherwise falls back to a default value of http://localhost:5000/api/).

The request is made using file_get_contents function that uses the $api_endpoint variable and user supplied URL from $_GET["url"].

Some analysis and transformations are performed on the received response that are later used in the markup to populate the page.

Let’s bring these services up in detached mode using docker-compose utility:

docker-compose up -d --build

Creating network "linkextractor_default" with the default driver

Pulling web (php:7-apache)...

7-apache: Pulling from library/php

... [OUTPUT REDACTED] ...

Status: Downloaded newer image for php:7-apache

Building api

Step 1/8 : FROM python:3

... [OUTPUT REDACTED] ...

Successfully built 1f419be1c2bf

Successfully tagged linkextractor-api:step4-python

Creating linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Creating linkextractor_api_1 ... done

This output shows that Docker Compose automatically created a network named linkextractor_default, pulled php:7-apache image from DockerHub, built api:python image using our local Dockerfile, and finally, spun two containers linkextractor_web_1 and linkextractor_api_1 that correspond to the two services we have defined in the YAML file above.

Checking for the list of running containers confirms that the two services are indeed running:

docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

268b021b5a2c php:7-apache "docker-php-entrypoi…" 3 minutes ago Up 3 minutes 0.0.0.0:80->80/tcp linkextractor_web_1

5bc266b4e43d linkextractor-api:step4-python "./main.py" 3 minutes ago Up 3 minutes 0.0.0.0:5000->5000/tcp linkextractor_api_1

We should now be able to talk to the API service as before:

curl -i http://localhost:5000/api/http://example.com/

To access the web interface click to open the Link Extractor.

Then fill the form with https://training.play-with-docker.com/ (or any HTML page URL of your choice) and submit to extract links from it.

We have just created an application with microservice architecture, isolating individual tasks in separate services as opposed to monolithic applications where everything is put together in a single unit. Microservice applications are relatively easier to scale, maintains, and move around. They also allow easy swapping of components with an equivalent service. More on that later.

Now, let’s modify the www/index.php file to replace all occurrences of Link Extractor with Super Link Extractor:

sed -i 's/Link Extractor/Super Link Extractor/g' www/index.php

Reloading the web interface of the application should now reflect this change in the title, header, and footer.

This is happening because the ./www folder is bind mounted inside of the container, so any changes made outside will reflect inside the container or the vice versa.

This approach is very helpful in development, but in the production environment we would prefer our Docker images to be self-contained.

Let’s revert these changes now to clean the Git tracking:

git reset --hard

Before we move on to the next step we need to shut these services down, but Docker Compose can help us take care of it very easily:

docker-compose down

Stopping linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Stopping linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Removing linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Removing linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Removing network linkextractor_default

In the next step we will add one more service to our stack and will build a self-contained custom image for our web interface service.

Step 5: Redis Service for Caching

Checkout the step5 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step5

tree

.

├── README.md

├── api

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── linkextractor.py

│ ├── main.py

│ └── requirements.txt

├── docker-compose.yml

└── www

├── Dockerfile

└── index.php

2 directories, 8 files

Some noticeable changes from the previous step are as following:

- Another

Dockerfileis added in the./wwwfolder for the PHP web application to build a self-contained image and avoid live file mounting - A Redis container is added for caching using the official Redis Docker image

- The API service talks to the Redis service to avoid downloading and parsing pages that were already scraped before

- A

REDIS_URLenvironment variable is added to the API service to allow it to connect to the Redis cache

Let’s first inspect the newly added Dockerfile under the ./www folder:

cat www/Dockerfile

FROM php:7-apache

LABEL maintainer="Sawood Alam <@ibnesayeed>"

ENV API_ENDPOINT="http://localhost:5000/api/"

COPY . /var/www/html/

This is a rather simple Dockerfile that uses the official php:7-apache image as the base and copies all the files from the ./www folder into the /var/www/html/ folder of the image.

This is exactly what was happening in the previous step, but that was bind mounted using a volume, while here we are making the code part of the self-contained image.

We have also added the API_ENDPOINT environment variable here with a default value, which implicitly suggests that this is an important information that needs to be present in order for the service to function properly (and should be customized at run time with an appropriate value).

Next, we will look at the API server’s api/main.py file where we are utilizing the Redis cache:

cat api/main.py

The file has many lines, but the important bits are as illustrated below:

redis_conn = redis.from_url(os.getenv("REDIS_URL", "redis://localhost:6379"))

# ...

jsonlinks = redis.get(url)

if not jsonlinks:

links = extract_links(url)

jsonlinks = json.dumps(links, indent=2)

redis.set(url, jsonlinks)

This time the API service needs to know how to connect to the Redis instance as it is going to use it for caching.

This information can be made available at run time using the REDIS_URL environment variable.

A corresponding ENV entry is also added in the Dockerfile of the API service with a default value.

A redis client instance is created using the hostname redis (same as the name of the service as we will see later) and the default Redis port 6379.

We are first trying to see if a cache is present in the Redis store for a given URL, if not then we use the extract_links function as before and populate the cache for future attempts.

Now, let’s look into the updated docker-compose.yml file:

cat docker-compose.yml

version: '3'

services:

api:

image: linkextractor-api:step5-python

build: ./api

ports:

- "5000:5000"

environment:

- REDIS_URL=redis://redis:6379

web:

image: linkextractor-web:step5-php

build: ./www

ports:

- "80:80"

environment:

- API_ENDPOINT=http://api:5000/api/

redis:

image: redis

The api service configuration largely remains the same as before, except the updated image tag and added environment variable REDIS_URL that points to the Redis service.

For the web service, we are using the custom linkextractor-web:step5-php image that will be built using the newly added Dockerfile in the ./www folder.

We are no longer mounting the ./www folder using the volumes config.

Finally, a new service named redis is added that will use the official image from DockerHub and needs no specific configurations for now.

This service is accessible to the Python API using its service name, the same way the API service is accessible to the PHP front-end service.

Let’s boot these services up:

docker-compose up -d --build

... [OUTPUT REDACTED] ...

Creating linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Creating linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Creating linkextractor_redis_1 ... done

Now, that all three services are up, access the web interface by clicking the Link Extractor.

There should be no visual difference from the previous step.

However, if you extract links from a page with a lot of links, the first time it should take longer, but the successive attempts to the same page should return the response fairly quickly.

To check whether or not the Redis service is being utilized, we can use docker-compose exec followed by the redis service name and the Redis CLI’s monitor command:

docker-compose exec redis redis-cli monitor

Now, try to extract links from some web pages using the web interface and see the difference in Redis log entries for pages that are scraped the first time and those that are repeated.

Before continuing further with the tutorial, stop the interactive monitor stream as a result of the above redis-cli command by pressing Ctrl + C keys while the interactive terminal is in focus.

Now that we are not mounting the /www folder inside the container, local changes should not reflect in the running service:

sed -i 's/Link Extractor/Super Link Extractor/g' www/index.php

Verify that the changes made locally do not reflect in the running service by reloading the web interface and then revert changes:

git reset --hard

Now, shut these services down and get ready for the next step:

docker-compose down

Stopping linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Stopping linkextractor_redis_1 ... done

Stopping linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Removing linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Removing linkextractor_redis_1 ... done

Removing linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Removing network linkextractor_default

We have successfully orchestrated three microservices to compose our Link Extractor application. We now have an application stack that represents the architecture illustrated in the figure shown in the introduction of this tutorial. In the next step we will explore how easy it is to swap components from an application with the microservice architecture.

Step 6: Swap Python API Service with Ruby

Checkout the step6 branch and list files in it.

git checkout step6

tree

.

├── README.md

├── api

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── Gemfile

│ └── linkextractor.rb

├── docker-compose.yml

├── logs

└── www

├── Dockerfile

└── index.php

3 directories, 7 files

Some significant changes from the previous step include:

- The API service written in Python is replaced with a similar Ruby implementation

- The

API_ENDPOINTenvironment variable is updated to point to the new Ruby API service - The link extraction cache event (HIT/MISS) is logged and is persisted using volumes

Notice that the ./api folder does not contain any Python scripts, instead, it now has a Ruby file and a Gemfile to manage dependencies.

Let’s have a quick walk through the changed files:

cat api/linkextractor.rb

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "sinatra"

require "open-uri"

require "uri"

require "nokogiri"

require "json"

require "redis"

set :protection, :except=>:path_traversal

redis = Redis.new(url: ENV["REDIS_URL"] || "redis://localhost:6379")

Dir.mkdir("logs") unless Dir.exist?("logs")

cache_log = File.new("logs/extraction.log", "a")

get "/" do

"Usage: http://<hostname>[:<prt>]/api/<url>"

end

get "/api/*" do

url = [params['splat'].first, request.query_string].reject(&:empty?).join("?")

cache_status = "HIT"

jsonlinks = redis.get(url)

if jsonlinks.nil?

cache_status = "MISS"

jsonlinks = JSON.pretty_generate(extract_links(url))

redis.set(url, jsonlinks)

end

cache_log.puts "#{Time.now.to_i}\t#{cache_status}\t#{url}"

status 200

headers "content-type" => "application/json"

body jsonlinks

end

def extract_links(url)

links = []

doc = Nokogiri::HTML(open(url))

doc.css("a").each do |link|

text = link.text.strip.split.join(" ")

begin

links.push({

text: text.empty? ? "[IMG]" : text,

href: URI.join(url, link["href"])

})

rescue

end

end

links

end

This Ruby file is almost equivalent to what we had in Python before, except, in addition to that it also logs the link extraction requests and corresponding cache events. In a microservice architecture application swapping components with an equivalent one is easy as long as the expectations of consumers of the component are maintained.

cat api/Dockerfile

FROM ruby:2.6

LABEL maintainer="Sawood Alam <@ibnesayeed>"

ENV LANG C.UTF-8

ENV REDIS_URL="redis://localhost:6379"

WORKDIR /app

COPY Gemfile /app/

RUN bundle install

COPY linkextractor.rb /app/

RUN chmod a+x linkextractor.rb

CMD ["./linkextractor.rb", "-o", "0.0.0.0"]

Above Dockerfile is written for the Ruby script and it is pretty much self-explanatory.

cat docker-compose.yml

version: '3'

services:

api:

image: linkextractor-api:step6-ruby

build: ./api

ports:

- "4567:4567"

environment:

- REDIS_URL=redis://redis:6379

volumes:

- ./logs:/app/logs

web:

image: linkextractor-web:step6-php

build: ./www

ports:

- "80:80"

environment:

- API_ENDPOINT=http://api:4567/api/

redis:

image: redis

The docker-compose.yml file has a few minor changes in it.

The api service image is now named linkextractor-api:step6-ruby, the port mapping is changed from 5000 to 4567 (which is the default port for Sinatra server), and the API_ENDPOINT environment variable in the web service is updated accordingly so that the PHP code can talk to it.

With these in place, let’s boot our service stack:

docker-compose up -d --build

... [OUTPUT REDACTED] ...

Successfully built b713eef49f55

Successfully tagged linkextractor-api:step6-ruby

Creating linkextractor_web_1 ... done

Creating linkextractor_api_1 ... done

Creating linkextractor_redis_1 ... done

We should now be able to access the API (using the updated port number):

curl -i http://localhost:4567/api/http://example.com/

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 96

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Server: WEBrick/1.4.2 (Ruby/2.5.1/2018-03-29)

Date: Mon, 24 Sep 2018 01:41:35 GMT

Connection: Keep-Alive

[

{

"text": "More information...",

"href": "http://www.iana.org/domains/example"

}

]

Now, open the web interface by clicking the Link Extractor and extract links of a few URLs. Also, try to repeat these attempts for some URLs. If everything is alright, the web application should behave as before without noticing any changes in the API service (which is completely replaced).

We can shut the stack down now:

docker-compose down

Since we have persisted logs, they should still be available after the services are gone:

cat logs/extraction.log

1537753295 MISS http://example.com/

1537753600 HIT http://example.com/

1537753635 MISS https://training.play-with-docker.com/

This illustrates that the caching is functional as the second attempt to the http://example.com/ resulted in a cache HIT.

In this step we explored the possibility of swapping components of an application with microservice architecture with their equivalents without impacting rest of the parts of the stack. We have also explored data persistence using bind mount volumes that persists even after the containers writing to the volume are gone.

So far, we have used docker-compose utility to orchestrate the application stack, which is good for development environment, but for production environment we use docker stack deploy command to run the application in a Docker Swarm Cluster.

It is left for you as an assignment to deploy this application in a Docker Swarm Cluster.

Conclusions

We started this tutorial with a simple Python script that scrapes links from a give web page URL. We demonstrated various difficulties in running the script. We then illustrated how easy to run and portable the script becomes onces it is containerized. In the later steps we gradually evolved the script into a multi-service application stack. In the process we explored various concepts of microservice architecture and how Docker tools can be helpful in orchestrating a multi-service stack. Finally, we demonstrated the ease of microservice component swapping and data persistence.